Note: I wrote this design piece around 7 months prior to publishing it here after a particularly frustrating string of experiences playing the utterly disappointing Gears of War 2.

To preface this piece I must declare that the original Gears of War was perhaps the most influential videogame for me personally in the last 5 years. It singlehandedly pulled me into the online console shooter market. Countless hours were spent rolling about with my shotgun, or pulling instinctive headshots with my sniper, to the point where I managed to max out all the achievement points on offer, a simple feat for most games but a “serious” medal of dedication in Gears’ case.

It’s safe to say however that the success of Gears multiplayer component was in fact an accidental one. The intention was to create a team based third person shooter that relied heavily on the franchise’s signature cover mechanic, and although that remained, certain emergent trends were brushing against the gameplay tide Epic intended to instil: the Gnasher shotgun being the primary offender.

Epic’s design and marketing centred on the Lancer assault rife, with its instantly recognisable chainsaw bayonet. Players spawned into the multiplayer fray with this weapon in hand, a decision which caused the amusing scenario of every player switching weapons immediately upon the beginning of a round, a trend as predictable as black clouds foreshadowing rain. The shotgun was the player’s choice, and the most effective weapon for medium to short range combat.

Not only this, but players would rush towards the specified weapon spawns on the map with the intention of picking up a “power weapon” most popularly the sniper rifle or the Boomshot, with the torque bow also proving a devastating tool in the right hands. And what would be lying on the ground in the wake of acquiring this power weapon? The Lancer.

Clearly Epic were perturbed by this weapon discrimination, the audience were neglecting their design decisions with no respect for the way they wanted their game to be played, and with Gears of War 2 they had their opportunity for retribution.

Amongst an influx of gameplay changes, one most affecting for hardcore Gears fans was the “nerfing” of the shotguns effectiveness. The shotgun was the fan’s baby, a tool that by now many players had grown so accustomed to after hours upon hours of play. Unfortunately Epic wanted to elevate the Lancers effectiveness in medium range combat situations, and in conjunction with the inclusion of stopping power, decided removing what made the shotgun such a popular weapon to use was the best way to do this.

Gears 2 presented a completely new shotgun. The spread was random, meaning the weapon couldn’t be relied upon in any situation, creating a scenario that left the player feeling cheated, with them performing the required moves in a combat situation to prevail, only to have the weapon act in opposition to the engrained experience they have been used to for hundreds of hours previously. What this also means is a distillation of skill, as a players skills cannot be relied on for victory, with this random spread preventing an accurate representation of their abilities. One feature of scientific experiments is “a fair test”, and if Gears 2’s multiplayer was such an experiment in player skill, as all successful competitive activites must be, it wouldn’t be considered a fair test.

Not only this but Epic diluted the shotguns co-operation with the roll mechanic. One popular aspect of Gears multiplayer for fans was the trend of shotgun rolling. This was once again a way to increase the gap between the skilled players and the less skilled ones. Skilled players were able to manoeuvre themselves into an advantage in a combat situation with a precise roll, as they were coming out of this roll they were then granted instant access to the shotguns devastating close quarters power, gibbing their opponent into bloodied pieces.

In Gears 2 however the decision was made to impose a handicap for these skilled players to stop them shotgun rolling. As players tried to fire coming out of their roll, nothing happened. An artificial time delay was put in place that made the player once again feel cheated, with on screen events contradicting the past experiences that have provided such gratifications over the past few years. The shotgun was gone. Its randomness and sluggishness slowed the pace down to a point that Gears 2 didn’t feel like Gears.

All in the name of the Lancer.

So why do players prefer to use the Shotgun, Sniper rifle, Boomshot and Torque Bow over the Lancer, or indeed the Hamerburst?

Instant Feedback: The visual and audible reward for a feat of immense skill and accomplishment in an online shooter.

In the original Gears, when a player hit the enemy flush with a blast from the Shotgun they would proceed to split open, becoming a series of meaty chunks. This provides immense pleasure to the player, an empowerment above and beyond anything offered by the Lancer with its lethargic spray of ineffective bullets. This reaction I will refer to as Instant Feedback. My most memorable experience of this came in a match on the map Rooftops. Whilst in cover against the rim of the maps central section, I noticed an enemy jogging towards my position, unaware of my lurking presence. I sent a Shotgun round blindly over my position aimed loosely at his waist. The shells from my Shotgun tore through his knees, ripping them from his waist and sending his torso flying opposite to the rest of his body. This is Instant Gratification at its most defined, and it makes the player feel good in a way not many games can.

Further examples are the visual and audible cues provided upon achieving a headshot. The visceral sound of imploding skull, combined with the fountain of blood and bone exploding from where the players head used to be provides this sense of Instant Feedback that the Lancer and Hammerburst just can’t, and that is the reason they are not a preferred weapon to use for the player, because frankly they are boring. The sense of empowerment as the player hits an opponent with a cleverly arced Boomshot, once again requiring skilful aiming over arbitrary spraying, as your adversary is split into numerous chunks and propelled 50 feet into the air, is massive. Instant Feedback at its finest, in the finest game to employ it ever created, the original Gears of War.

Now how can you go about incentivising the Lancer with Instant Feedback without treading into the realms of ridiculousness, obviously you cannot have the player exploding in a fit of gore when shot by a few rifle rounds.

Interestingly, my theory of Instant Feedback can be noticed in shooters of a less visceral nature in other forms. For example, in the game Halo 3, the Battle Rifle is the preferred weapon of choice for skilled players as it rewards a good aim. The gun fires in a concentrated trajectory, travelling exactly where the player is aiming. Not only this but its semi automatic nature means it requires a physical pull of the trigger on each burst, transmitting the players inputs into specific, instant effects on screen. Furthermore when the visual cue appears that the enemy shield has dropped, the player knows he is one calculated headshot away from that always-gratifying ragdoll effect.

To relate this back to the Lancer, a system could be implemented whereby the Lancer and Hammerburst were combined to create a semi automatic mid ranged rifle that uses Instant Feedback to empower the player and choose it over the shotgun and the sniper rifle. The weapon should require a specific number of shots to get the enemy to a point where he is one shot away from an instant headshot., similar to that of a sniper rifle or a Boltok. For example, in Halo 3 the term “4-shot” relates to the amount of shots it takes to drop a fully shielded opponent, this could translate into the newly balanced incarnation of the Lancer. Furthermore the visual effect of the bullet penetrating the opponents armour and flesh must be visually appealing, spraying smoke and blood from the front and the rear, painting objects behind the enemy in a moist crimson. Not only this but the sound effect of the rifle must be chunky and meaty. It must crack and echo upon the surroundings, an audible cue to opponents that danger is close. Not to mention the audio effect as the bullet penetrates the opponent must sound like high velocity meeting flesh.

These audio effects are massively important to this overall pleasure of Instant Feedback. Imagine them combo-ing so to speak, whereby you are greeted to the sound of bullet hitting flesh once, twice then a third time, finally to hear the sound of the headshot, as bone cracks and explodes in a visceral fashion, feedback to the player that he has just accomplished something of serious skill, equal to a shotgun roll or a long ranged sniper headshot.

In its current form the Lancer is dull. It sprays puny bullets at a chunk of meat with little Instant Feedback. Even once the player has fired a significant amount of bullets at the enemy, they simply fall to their hands and knees, denying the player of any Instant Feedback in a visual sense, unlike the other weapons.

If you want to elevate specific sections of the sandbox, you must make them equally appealing, and with Instant Feedback you can do this. It is not a case of removing features to make other weapons bad qualities seem acceptable, it is about raising the Instant Feedback of the underwhelming weapons to a point that matches the rest of the games arsenal in its own specified role on the battlefield, in the Lancers case, mid ranged combat.

Friday, 1 October 2010

Monday, 12 July 2010

Schadenfreude

Hardcore - The most active, committed or doctrinaire members of a group or movement

There are hardcore music enthusiasts, bird watchers, book collectors and historians. For the majority of my conscious life I have strongly considered myself a "hardcore" gamer. "Hardcore" is a word that when combined with "gamer" is likely to produce involuntary sniggering and ignorance from a group of hardcore cunts. As the definition implies, I like to think myself commited and passionate enough to enjoy any videogame in some way. Just as a music enthusiast can appreciate the artistic endeavour of one man creating percussion on a block of cheese, I consider myself able to appreciate almost any form of videogame. Or at least that's what I thought, it turns out some are simply too hardcore for me.

From Software is an interesting development studio. They have developed a wealth of different IPs on a breadth of platforms, although they are most recognised for their work on two in particular, Kings Field and Armoured Core. Their latest IP however, the one that forced me to reconsider my place in the universe, is called Demon Souls. Just as hardcore Film enthusiasts would watch French New Wave films to prove their specialist knowledge, hardcore gamers have adopted Demon Souls as their poster child. And by all accounts Demon Souls too, like other adverts for hardcore movements is completely foreign. Drenched in Japanese design, Demon Souls is a linear action RPG like no other.

Most videogames treat death with a slap on the wrist. If you die in a conventional videogame, you witness a brief "You are dead" screen whilst the game reloads 5 minutes before you met your untimely end. The developer is basically chuckling like a patronising mother whilst proclaiming "Oooo aren't you clumsy". Demon Souls however is the pushy father who trains his son to play the piano 12 hours a day until he has mastered a particular song. He will not get it wrong, and if he does he will be punished. Every enemy in Demon Souls has the ability to kill you within single digits of seconds. If you do not have your shield at the ready and facing the direction your enemy is attacking from, you will die. And if you have spent the last hour trekking through the games depressing, melancholy dungeons only to be killed, you must start back from the levels beginning with all of the enemies you have defeated now out for revenge. And it gets worse. Each enemy you kill drops his soul for you to collect. These souls act as a necessary currency in order for you to buy, repair and upgrade your gear and stats. If you wish to collect all the souls you were holding once you died you must fight your way back to your body, where you must once again face the thing that killed you the first time. Should you die again your souls will be lost forever.

I mentioned earlier that Demon Souls is a game littered with Japanese design. This is true, however part of the reason for Demon Souls cult success is its amalgamation of other design cultures into the game. Most Japanese developers shudder at the words "online connectivity". From Software however simply grin. Demon Souls features online capabilities completely unique to the game, ones that consequently fit perfectly into the games ethos. Should you die, you may leave messages to other players about the events that caused your death in a bid to help other players survive. Alternatively you may gain a sadistic pleasure from providing false information that in the context of Demon Souls unforgiving design will no doubt kill whoever follows it. Not only that but Demon Souls will often throw an opposing player into your game world who is intent on killing you. These opposing players are players who have died and are looking to regain all their souls, interestingly should they kill you they will gain all their souls back instantly, causing a tense stand off in which one player desperately wants to avoid death whilst the other goes on the attack.

Demon Souls is unique. It is a game that challenges the player and doesn't accommodate for the lowest common denominator. It is a test of a gamer's skill, dexterity and patience. It pushes the player to get it right in a bid to hone their abilities, relying on muscle memory as much as quick thinking. Unfortunately Demon Souls isn't fun. It is tense, scary and more frustrating than a Manchester United replica shirt. For that reason I couldn't appreciate it like others could, perhaps I wasn't hardcore enough.

There are hardcore music enthusiasts, bird watchers, book collectors and historians. For the majority of my conscious life I have strongly considered myself a "hardcore" gamer. "Hardcore" is a word that when combined with "gamer" is likely to produce involuntary sniggering and ignorance from a group of hardcore cunts. As the definition implies, I like to think myself commited and passionate enough to enjoy any videogame in some way. Just as a music enthusiast can appreciate the artistic endeavour of one man creating percussion on a block of cheese, I consider myself able to appreciate almost any form of videogame. Or at least that's what I thought, it turns out some are simply too hardcore for me.

From Software is an interesting development studio. They have developed a wealth of different IPs on a breadth of platforms, although they are most recognised for their work on two in particular, Kings Field and Armoured Core. Their latest IP however, the one that forced me to reconsider my place in the universe, is called Demon Souls. Just as hardcore Film enthusiasts would watch French New Wave films to prove their specialist knowledge, hardcore gamers have adopted Demon Souls as their poster child. And by all accounts Demon Souls too, like other adverts for hardcore movements is completely foreign. Drenched in Japanese design, Demon Souls is a linear action RPG like no other.

Most videogames treat death with a slap on the wrist. If you die in a conventional videogame, you witness a brief "You are dead" screen whilst the game reloads 5 minutes before you met your untimely end. The developer is basically chuckling like a patronising mother whilst proclaiming "Oooo aren't you clumsy". Demon Souls however is the pushy father who trains his son to play the piano 12 hours a day until he has mastered a particular song. He will not get it wrong, and if he does he will be punished. Every enemy in Demon Souls has the ability to kill you within single digits of seconds. If you do not have your shield at the ready and facing the direction your enemy is attacking from, you will die. And if you have spent the last hour trekking through the games depressing, melancholy dungeons only to be killed, you must start back from the levels beginning with all of the enemies you have defeated now out for revenge. And it gets worse. Each enemy you kill drops his soul for you to collect. These souls act as a necessary currency in order for you to buy, repair and upgrade your gear and stats. If you wish to collect all the souls you were holding once you died you must fight your way back to your body, where you must once again face the thing that killed you the first time. Should you die again your souls will be lost forever.

I mentioned earlier that Demon Souls is a game littered with Japanese design. This is true, however part of the reason for Demon Souls cult success is its amalgamation of other design cultures into the game. Most Japanese developers shudder at the words "online connectivity". From Software however simply grin. Demon Souls features online capabilities completely unique to the game, ones that consequently fit perfectly into the games ethos. Should you die, you may leave messages to other players about the events that caused your death in a bid to help other players survive. Alternatively you may gain a sadistic pleasure from providing false information that in the context of Demon Souls unforgiving design will no doubt kill whoever follows it. Not only that but Demon Souls will often throw an opposing player into your game world who is intent on killing you. These opposing players are players who have died and are looking to regain all their souls, interestingly should they kill you they will gain all their souls back instantly, causing a tense stand off in which one player desperately wants to avoid death whilst the other goes on the attack.

Demon Souls is unique. It is a game that challenges the player and doesn't accommodate for the lowest common denominator. It is a test of a gamer's skill, dexterity and patience. It pushes the player to get it right in a bid to hone their abilities, relying on muscle memory as much as quick thinking. Unfortunately Demon Souls isn't fun. It is tense, scary and more frustrating than a Manchester United replica shirt. For that reason I couldn't appreciate it like others could, perhaps I wasn't hardcore enough.

Wednesday, 9 June 2010

I'm Not a Puppet, I'm a Real Boy

One contradiction present within videogames is that of providing the player with more "freedom" in their actions yet limiting their inputs to a pre-determined set of functions. For example, in my previous blog entry I focused on Red Dead Redemption, a game that offers undeniable scope in its vast Western environment yet constrains the player to a handful of ways in which they can interact with it. Red Dead Redemption is a game that took a team of hundreds, five years to produce yet the game repeats a limited set of mechanics to push the player through the narrative. Riding horses, shooting guns and lassoing criminals are all accepted forms of interaction in Red Dead, programmed onto the game controller for the players disposal. Other, more abstract forms of interacting with the game world however are not performable as the development team could not afford to devote a specific button on the controller to the sole action of "laughing" for example. When I saw a drunk redneck stumble off a balcony due to his intoxicated state I wished to laugh at him in the game in order to highlight his stupidity, perhaps provoking a fight, however I didn't have the option to laugh, so I shot him instead. This is a quick and dirty example of my limited ability to interact with the game world in Red Dead Redemption.

Some games try to offer these abstract interactions, albeit with limited success. Fable for example, a game stuffed with British humour, allows the player to perform a number of contextual actions with the use of the D-Pad. Laughing, shouting, kissing and farting are all options available to the player when interacting with the games NPC (non playable character) population. Unfortunately it's not just the ability to perform such an immature function that allows the player to be immersed into the games simulacra, it is the way the simulation responds. Yet again a quick and dirty example: I am talking to a key character who is giving me a quest, she is relying on my courage and skill to save the entire world that she holds so dear to her heart, yet for the past 3 minutes I have been releasing a continuous burst of audibly horrific farts. Why is she still giving me such responsibility? Surely she would have turned and walked away, identifying me as the socially inept retard that I am. But no, the games inability to respond correctly to such non linear interactions highlights the games simulation. I realise I have spent the last 3 minutes virtually farting, thus causing me to turn off my Xbox in self disgust.

Some genres focus solely on the idea of non linear interactions however, the point and click adventure. Take for example a game that I have been playing recently, Machinarium. This is an independent game created by seven Czechoslovakians funded by their own personal savings. When contrasted with the likes of Red Dead Redemption it seems illogical that it should offer a wider array of experiences. But it does. Machinarium follows the exploits of a robot after he is exiled from his home city, it is up to the player to guide the robot (Josef) back into the city and to overthrow a gang of evil robots known as the Brotherhood. The games control scheme lies solely on the mouse. You click on objects to interact with them. You can raise and lower Josef's height if necessary and must solve constant puzzles in order to continue. Here the audience's pleasure doesn't come from the visceral nature of shooting an outlaw off of his horse ala Red Dead, but rather with the cerebral nature of the games structure, forcing you to think logically and carefully about how to navigate through the game. The control schemes ambiguity is what makes it so entertaining. Of course this brief summary is not quick nor dirty enough, so let me fix that:

I am locked in a prison cell with a depressed looking robot. The cell is small, with a toilet, a light, a small hole in the wall and green moss covering the walls. I engage in a conversation with the melancholy robot, emitting a series of beeps and boops, both equally indecipherable. A thought bubble emits from the head of the robot, a spliff contained within. So now I have my task, i must get my friend a spliff, for what purpose I don't really know. I rip off a piece of toilet roll and store it in my chest, this will obviously form the exterior skin of my narcotic creation. I raise Josef up and scoop some green moss from the cell wall, storing it within myself. Now at first I thought this was it, I tried to combine the two items to form the spliff that would allow me to progress, Josef shook his head in a defiant fashion. What had I missed? I then placed the moss on the cell light, frying it into a brownish subtance, this was it. I was able to combine the two items which I selflessly gave to the robot. In his delight at smoking such a beautifully crafted item his arm fell off. I picked it up and stored it in my chest, it's safe to say the arm would come in handy later. I then went on to break out of the cell

This is just one example that highlights how the game allows you to interact so extensively with the game world, more so than most big budget releases. It's alright spending the time and resources building such huge, detailed environments, but if you can't interact with them what's the point.

Some games try to offer these abstract interactions, albeit with limited success. Fable for example, a game stuffed with British humour, allows the player to perform a number of contextual actions with the use of the D-Pad. Laughing, shouting, kissing and farting are all options available to the player when interacting with the games NPC (non playable character) population. Unfortunately it's not just the ability to perform such an immature function that allows the player to be immersed into the games simulacra, it is the way the simulation responds. Yet again a quick and dirty example: I am talking to a key character who is giving me a quest, she is relying on my courage and skill to save the entire world that she holds so dear to her heart, yet for the past 3 minutes I have been releasing a continuous burst of audibly horrific farts. Why is she still giving me such responsibility? Surely she would have turned and walked away, identifying me as the socially inept retard that I am. But no, the games inability to respond correctly to such non linear interactions highlights the games simulation. I realise I have spent the last 3 minutes virtually farting, thus causing me to turn off my Xbox in self disgust.

Some genres focus solely on the idea of non linear interactions however, the point and click adventure. Take for example a game that I have been playing recently, Machinarium. This is an independent game created by seven Czechoslovakians funded by their own personal savings. When contrasted with the likes of Red Dead Redemption it seems illogical that it should offer a wider array of experiences. But it does. Machinarium follows the exploits of a robot after he is exiled from his home city, it is up to the player to guide the robot (Josef) back into the city and to overthrow a gang of evil robots known as the Brotherhood. The games control scheme lies solely on the mouse. You click on objects to interact with them. You can raise and lower Josef's height if necessary and must solve constant puzzles in order to continue. Here the audience's pleasure doesn't come from the visceral nature of shooting an outlaw off of his horse ala Red Dead, but rather with the cerebral nature of the games structure, forcing you to think logically and carefully about how to navigate through the game. The control schemes ambiguity is what makes it so entertaining. Of course this brief summary is not quick nor dirty enough, so let me fix that:

I am locked in a prison cell with a depressed looking robot. The cell is small, with a toilet, a light, a small hole in the wall and green moss covering the walls. I engage in a conversation with the melancholy robot, emitting a series of beeps and boops, both equally indecipherable. A thought bubble emits from the head of the robot, a spliff contained within. So now I have my task, i must get my friend a spliff, for what purpose I don't really know. I rip off a piece of toilet roll and store it in my chest, this will obviously form the exterior skin of my narcotic creation. I raise Josef up and scoop some green moss from the cell wall, storing it within myself. Now at first I thought this was it, I tried to combine the two items to form the spliff that would allow me to progress, Josef shook his head in a defiant fashion. What had I missed? I then placed the moss on the cell light, frying it into a brownish subtance, this was it. I was able to combine the two items which I selflessly gave to the robot. In his delight at smoking such a beautifully crafted item his arm fell off. I picked it up and stored it in my chest, it's safe to say the arm would come in handy later. I then went on to break out of the cell

This is just one example that highlights how the game allows you to interact so extensively with the game world, more so than most big budget releases. It's alright spending the time and resources building such huge, detailed environments, but if you can't interact with them what's the point.

Thursday, 3 June 2010

Rockstar Redeemed... Kind Of

When video games were first created, they were structured around the player advancing to higher levels which in turn increased the difficulty, eventually forcing the player to abandon his progress and accept defeat, only to try again another day. This system would keep early gamers coming back time after time to drop more money into a never ending series of challenges. However, upon gaming growing from the leaderboard centric experiences of old to the blockbuster experiences of today something had to be added, a narrative.

One problem with stitching a linear narrative upon a non linear experience is that of contradiction. If I the player wish to progress in this non linear game then I must conform to the linearity imposed by the narrative. Another problem brought about by developers having to provide context for the players actions is that of the actions themselves. Think back to Tetris, a game unarguably entertaining, however a narrative simply could not be attached to the games underlying mechanics, to do so would be dumb.

Long renowned as the kings of the non linear experience, Rockstar (creators of the GTA franchise) have consistently struggled with some of the problems brought about by a Narrative. The experience must include the trite increase in difficulty, an established videogame trope, whilst also telling a balanced narrative. For those unaware of the narrative arc as proposed by Todorov, after the climax there must be a sense of equilibrium, a calm indicating that the problems and complications presented within the narrative have been defeated. Obviously this calm doesn't fit with the ramping difficulty previously mentioned.

One (of many) criticism levelled at Rockstar's latest entry into the Grand Theft Auto franchise (GTA IV) was that the protagonist's motives weren't fitting with the themes the game proposed and the ideologies of the character himself. The main protagonist Niko would claim to search for a better life, promoting peace over violence during the games early hours whilst happily accepting tasks which required him to murder hundreds of people for the promise of money. This contradiction (a recurring theme it seems) alienated players from Niko's narrative struggle which undermined many of the things the game aimed to achieve.

So it was Rockstar San Diego's turn to try and repair some of the bad reputation Rockstar North garnered with GTA IV, and how ironic they would attempt to do so with Red Dead Redemption. One element immediately in RDR's favour was that the theme of redemption was ambiguous enough to allow Rockstar the freedom to create solid game mechanics without impeding on the story they are trying to tell.

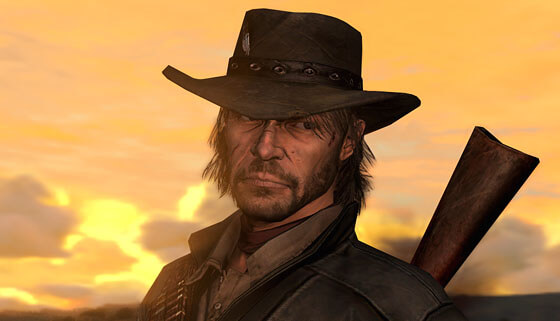

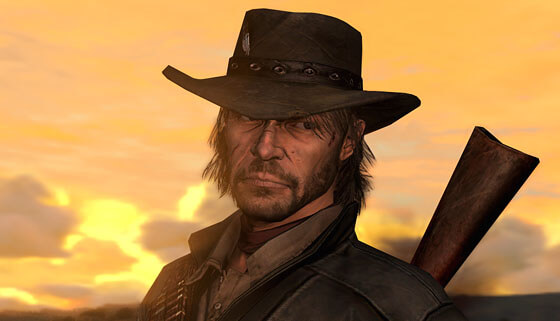

Red Dead Redemption follows protagonist John Marston, a former gang member who has since started a new life with his wife and son. However, the government aren't keen on letting John forget his former life so easily, blackmailing him into hunting down his former gang members to make the wild west a safer place, under threat that if he declines they will murder his family. This narrative naturally allows for the protagonist to kill many people and accept instruction from others due to the lives of his loved ones hanging in the balance. And so RDR immediately does what GTA IV couldn't, creates a narrative that provides context for the players actions without it feeling forced or implausible.

The main body of the game isn't why i came away so impressed with RDR however. Yes there is the fact that you have to hunt down your former gang members to see your family again, which is entertaining, but what follows is why I believe RDR to be a masterpiece. I mentioned earlier that games do not run the full length of the narrative arc, finishing with the climax rather than the new equilibrium, well RDR changes this. Upon hunting down your former gang members you are reunited with your family and left alone to live out your life on a farm. The theme of redemption doesn't just translate to John's struggle to leave his past life, it also relates to John's struggle to be a good father and husband, and the games final act allows you to do just this. Forgetting the need to keep the difficulty at an all time high, the games final chapter for the most part relaxes the pace whilst challenging you to tender the farm, deliver corn, take your son hunting and herd cattle, all for the benefit of your family. I won't spoil the games final moments but I will say that this is one title which leaves the player feeling ultimately satisfied with the characters and narrative throughout the ENTIRE experience. Not a feat many have accomplished.

Whilst videogames and narrative don't exactly go hand in hand, Rockstar San Diego proved it's not impossible to place a satisfying narrative within a non linear experience. RDR presents a narrative that is both consistent with the game mechanics and one allowed to fully flower come the games final moments, leaving the player speechless once the credits role. Rockstar redeemed then.

One problem with stitching a linear narrative upon a non linear experience is that of contradiction. If I the player wish to progress in this non linear game then I must conform to the linearity imposed by the narrative. Another problem brought about by developers having to provide context for the players actions is that of the actions themselves. Think back to Tetris, a game unarguably entertaining, however a narrative simply could not be attached to the games underlying mechanics, to do so would be dumb.

Long renowned as the kings of the non linear experience, Rockstar (creators of the GTA franchise) have consistently struggled with some of the problems brought about by a Narrative. The experience must include the trite increase in difficulty, an established videogame trope, whilst also telling a balanced narrative. For those unaware of the narrative arc as proposed by Todorov, after the climax there must be a sense of equilibrium, a calm indicating that the problems and complications presented within the narrative have been defeated. Obviously this calm doesn't fit with the ramping difficulty previously mentioned.

One (of many) criticism levelled at Rockstar's latest entry into the Grand Theft Auto franchise (GTA IV) was that the protagonist's motives weren't fitting with the themes the game proposed and the ideologies of the character himself. The main protagonist Niko would claim to search for a better life, promoting peace over violence during the games early hours whilst happily accepting tasks which required him to murder hundreds of people for the promise of money. This contradiction (a recurring theme it seems) alienated players from Niko's narrative struggle which undermined many of the things the game aimed to achieve.

So it was Rockstar San Diego's turn to try and repair some of the bad reputation Rockstar North garnered with GTA IV, and how ironic they would attempt to do so with Red Dead Redemption. One element immediately in RDR's favour was that the theme of redemption was ambiguous enough to allow Rockstar the freedom to create solid game mechanics without impeding on the story they are trying to tell.

Red Dead Redemption follows protagonist John Marston, a former gang member who has since started a new life with his wife and son. However, the government aren't keen on letting John forget his former life so easily, blackmailing him into hunting down his former gang members to make the wild west a safer place, under threat that if he declines they will murder his family. This narrative naturally allows for the protagonist to kill many people and accept instruction from others due to the lives of his loved ones hanging in the balance. And so RDR immediately does what GTA IV couldn't, creates a narrative that provides context for the players actions without it feeling forced or implausible.

The main body of the game isn't why i came away so impressed with RDR however. Yes there is the fact that you have to hunt down your former gang members to see your family again, which is entertaining, but what follows is why I believe RDR to be a masterpiece. I mentioned earlier that games do not run the full length of the narrative arc, finishing with the climax rather than the new equilibrium, well RDR changes this. Upon hunting down your former gang members you are reunited with your family and left alone to live out your life on a farm. The theme of redemption doesn't just translate to John's struggle to leave his past life, it also relates to John's struggle to be a good father and husband, and the games final act allows you to do just this. Forgetting the need to keep the difficulty at an all time high, the games final chapter for the most part relaxes the pace whilst challenging you to tender the farm, deliver corn, take your son hunting and herd cattle, all for the benefit of your family. I won't spoil the games final moments but I will say that this is one title which leaves the player feeling ultimately satisfied with the characters and narrative throughout the ENTIRE experience. Not a feat many have accomplished.

Whilst videogames and narrative don't exactly go hand in hand, Rockstar San Diego proved it's not impossible to place a satisfying narrative within a non linear experience. RDR presents a narrative that is both consistent with the game mechanics and one allowed to fully flower come the games final moments, leaving the player speechless once the credits role. Rockstar redeemed then.

Wednesday, 12 May 2010

Put Your Gut To One Side, This Is A Good Thing

Note - This discussion contains American metrics, if your patriotism prevents you from digesting them, leave now.

As audiences we often feel a sense of righteousness. We feel the Institutions creating the products we consume in fact owe us some indescribable debt. This is only half right. As paying consumers, institutions owe us the product we pay for which incidentally has been funded on the good faith of our cash. So what happens when we, the consumers don't pay the institutions the money they require to fund the development of such a product? Debt happens. And in 2010s flakey economic climate this is too much of a risk, thus game conglomerate EA steps in to continue it's long drawn battle against video game piracy and used game sales.

To clarify, the profit from every new video game we purchase from a retailer is divided up and spread between all parties involved in its production and distribution, fairly accounting for the costs associated with its existence. However, for every used game sold the profit is owned by the retailer themselves, cutting the content creators from the economic lifeline they require to remain productive. Ever been in a shop and seen a used game £5 cheaper than its freshly shrink-wrapped counterpart, well in fact by opting for the cheaper version you aren't rewarding the people responsible for its creation.

Luckily for EA there are things they can do to combat this damaging scheme. One such method is their recently devised "Project 10 Dollar", a service offered to new game purchasers in which they can unlock additional content to that on the disk by means of a single use redeemable code. This repositions the value of new games versus used ones in the audiences minds with the aim of incentivising new game sales to those pesky pre-owners. And now, EA has gone one step further with the "EA Sports Online Pass". Beginning soon, new EA Sports titles will come with a redeemable code that offers online features and content to those who use it. Consumers who do not buy a new copy of the game will not in fact receive such a code, thus meaning they will have to pay a $10 fee for the privilege. To clarify, EA are preventing used game purchasers from taking their titles online without an added subscription fee.

For consumers then, EA are seemingly removing features they have always had access to in an attempt to make you pay more money. Yes that is one way of viewing such a situation. Alternatively, EA are ensuring that they receive enough money from their games in order to pay for the cost of upholding the servers which enable your online entertainment. It is economically unfeasible to expect EA to maintain online servers for consumers who have payed them zero money for their product.

This announcement has caused uproar, complaints, petty dummy throwing and squabblery to many internet overlords and armchair analysts across the globe, but in fact seems extremely reasonable. If you put your initial gut reaction to one side and examine the details behind the announcement, EA are doing exactly what they should, making sure that their products remain economically viable in a digital age.

As audiences we often feel a sense of righteousness. We feel the Institutions creating the products we consume in fact owe us some indescribable debt. This is only half right. As paying consumers, institutions owe us the product we pay for which incidentally has been funded on the good faith of our cash. So what happens when we, the consumers don't pay the institutions the money they require to fund the development of such a product? Debt happens. And in 2010s flakey economic climate this is too much of a risk, thus game conglomerate EA steps in to continue it's long drawn battle against video game piracy and used game sales.

To clarify, the profit from every new video game we purchase from a retailer is divided up and spread between all parties involved in its production and distribution, fairly accounting for the costs associated with its existence. However, for every used game sold the profit is owned by the retailer themselves, cutting the content creators from the economic lifeline they require to remain productive. Ever been in a shop and seen a used game £5 cheaper than its freshly shrink-wrapped counterpart, well in fact by opting for the cheaper version you aren't rewarding the people responsible for its creation.

Luckily for EA there are things they can do to combat this damaging scheme. One such method is their recently devised "Project 10 Dollar", a service offered to new game purchasers in which they can unlock additional content to that on the disk by means of a single use redeemable code. This repositions the value of new games versus used ones in the audiences minds with the aim of incentivising new game sales to those pesky pre-owners. And now, EA has gone one step further with the "EA Sports Online Pass". Beginning soon, new EA Sports titles will come with a redeemable code that offers online features and content to those who use it. Consumers who do not buy a new copy of the game will not in fact receive such a code, thus meaning they will have to pay a $10 fee for the privilege. To clarify, EA are preventing used game purchasers from taking their titles online without an added subscription fee.

For consumers then, EA are seemingly removing features they have always had access to in an attempt to make you pay more money. Yes that is one way of viewing such a situation. Alternatively, EA are ensuring that they receive enough money from their games in order to pay for the cost of upholding the servers which enable your online entertainment. It is economically unfeasible to expect EA to maintain online servers for consumers who have payed them zero money for their product.

This announcement has caused uproar, complaints, petty dummy throwing and squabblery to many internet overlords and armchair analysts across the globe, but in fact seems extremely reasonable. If you put your initial gut reaction to one side and examine the details behind the announcement, EA are doing exactly what they should, making sure that their products remain economically viable in a digital age.

Monday, 19 April 2010

Bittersweet Symphony

As a preface I must clarify that I applaud developers for trying out new things, however so long as these "new things" work. By "work" I mean that they either fit the franchise or genre they are inserted into, or that they don't impede on the games overall transmission of fun, and in Splinter Cell: Convictions case, Ubisoft Montreal (the team behind the good ones) are massively guilty of ignoring the former.

This isn't Splinter Cell as you may know it.

To an outsider like myself it appears the team in Montreal sat down together during a pivotal moment in Convictions publicly troubled development cycle and watched the Bourne trilogy with their pants off. During this seminal moment they came so hard whilst watching Matt Damon that they decided to forgo all inroads the previous Splinter Cells had made into the stealth genre and made... an action game. Sam Fisher no longer asks questions, he no longer dispatches enemies from the shadows with a disabling blow to the head, he whips out a pistol an tears shit up. For all intensive purposes they may as well have called it Jason Bourne: Conviction.

After killing someone with your bear hands, you then get the ability to mark a bunch of enemies. Do you get excited in films when the protagonist enters a room only to dispatch 10 guys with a single, concise bullet to the brain? Well if you do you're going to love conviction. As much as it often feels like cheating there is no denying the mark and execute mechanic empowers the player and makes you feel like Jack Bauer's illegitimate son. This is the perfect example of everything wrong about the game, although at times it may be heaps of fun, it is not what it says on the cover, it is not Splinter Cell.

See this is one example from a long list of the changes made to conviction. You no longer need to sneak around. You no longer have to shoot out lights. You no longer have to move bodies. And while on paper these changes sound like good things, which in many ways they are, they are equally something completely different to Splinter Cells ethos. They are like putting jelly in a kebab, completely wrong.

As much as I wanted to love Conviction, and as much as I enjoyed it, I will not call it Splinter Cell.

This isn't Splinter Cell as you may know it.

To an outsider like myself it appears the team in Montreal sat down together during a pivotal moment in Convictions publicly troubled development cycle and watched the Bourne trilogy with their pants off. During this seminal moment they came so hard whilst watching Matt Damon that they decided to forgo all inroads the previous Splinter Cells had made into the stealth genre and made... an action game. Sam Fisher no longer asks questions, he no longer dispatches enemies from the shadows with a disabling blow to the head, he whips out a pistol an tears shit up. For all intensive purposes they may as well have called it Jason Bourne: Conviction.

After killing someone with your bear hands, you then get the ability to mark a bunch of enemies. Do you get excited in films when the protagonist enters a room only to dispatch 10 guys with a single, concise bullet to the brain? Well if you do you're going to love conviction. As much as it often feels like cheating there is no denying the mark and execute mechanic empowers the player and makes you feel like Jack Bauer's illegitimate son. This is the perfect example of everything wrong about the game, although at times it may be heaps of fun, it is not what it says on the cover, it is not Splinter Cell.

See this is one example from a long list of the changes made to conviction. You no longer need to sneak around. You no longer have to shoot out lights. You no longer have to move bodies. And while on paper these changes sound like good things, which in many ways they are, they are equally something completely different to Splinter Cells ethos. They are like putting jelly in a kebab, completely wrong.

As much as I wanted to love Conviction, and as much as I enjoyed it, I will not call it Splinter Cell.

Sunday, 4 April 2010

By Design

Have you ever had the displeasure of sitting through a traffic jam, only to realise when it clears that there was no discernible cause? Well, whilst watching The One Show, Adrian Chiles and his permanently hollow face took the time to explain this phenomenon known colloquially as the phantom traffic jam.

What actually happens, interestingly, is that as the motorway twists and curls endlessly to it's destination, the cars travelling swiftly upon it aren't moving at equal velocities, causing vehicles to slow down at certain points to accommodate other driver's unique traits and average speeds. This inconsistency in speed sends a rippling effect backwards down the motorway as all vehicles must bunch to prevent mass collision following the sudden halt in parallel proceedings, catalysing the phantom traffic jam.

Now, follow me into the most uncomfortable of metaphors. Imagine the motorway is actually the fun a video game transmits to its audience, the smoother the journey, the more fun the player receives. Each small detail such as an inconsistency in speed can have a rippling effect, leading to a metaphorical traffic jam, preventing the player from having a "fun" experience.

It is these philosophies that the most successful designers apply to their video games, most notably Bungie. Bungie are a studio that don't just aim to prevent traffic jams, they delicately measure the road surface to ensure a smooth journey, and erect signs to subliminally guide players on their way, in a direction they didn't even intend to travel. They are the masters of "fun" game design, the "pukka pies" of game studios: no compromise.

What better way to illustrate my point, apart from a fucking motorway metaphor, than a pdf file.

In Bungie land, changing the intermission between each shot with the Sniper Rifle from 0.5 seconds to 0.7 is enough to keep the motorway in a constant flow of "fun". The above PDF details Bungie's lead gameplay designer Jamie Griesemer's philosophy of breaking game design down to micro levels of detail, each of which build up to form one fun experience.

In the PDF Griesemer refers to the Bungie trademarked "30 seconds of fun" gameplay loop that if correctly utilised can keep providing audiences with gratifications in a continuous cycle. Referring back to the motorway metaphor, if the traffic keeps stalling then the driver is more likely to take the next exit, or in Bungie's case switch to a different game altogether. And it is Griesemer's job as Lead Gameplay Designer to keep the audience playing, at any cost.

In a recent Bungie podcast, when asked about the change in FOV (the players field of view) for Bungie's latest title, Sandbox designer Sage Merril discussed the many aspects that have to be considered when changing a shooters FOV, aspects that to me the ignorant player, had never crossed my mind. Firstly there is scale, what goes unnoticed in first person shooters is that the scale of the environments have to appear correctly within the players field of view, whilst also matching up to other minute elements of the game, such as grenade arc and line of sight. The field of view can also change a player's perception of speed, changing the entire pace of a game, a potentially catastrophic accident waiting to happen if not properly balanced.

By balancing these minute details, Bungie are able to stay rooted at the forefront of the first person shooter genre today, as it is these design philosophies and details which prevail above all else to keep the player engaged within the game. Fancy graphics and experience points may be a tasty substitute but they are no match for good old fashioned fun.

What actually happens, interestingly, is that as the motorway twists and curls endlessly to it's destination, the cars travelling swiftly upon it aren't moving at equal velocities, causing vehicles to slow down at certain points to accommodate other driver's unique traits and average speeds. This inconsistency in speed sends a rippling effect backwards down the motorway as all vehicles must bunch to prevent mass collision following the sudden halt in parallel proceedings, catalysing the phantom traffic jam.

Now, follow me into the most uncomfortable of metaphors. Imagine the motorway is actually the fun a video game transmits to its audience, the smoother the journey, the more fun the player receives. Each small detail such as an inconsistency in speed can have a rippling effect, leading to a metaphorical traffic jam, preventing the player from having a "fun" experience.

It is these philosophies that the most successful designers apply to their video games, most notably Bungie. Bungie are a studio that don't just aim to prevent traffic jams, they delicately measure the road surface to ensure a smooth journey, and erect signs to subliminally guide players on their way, in a direction they didn't even intend to travel. They are the masters of "fun" game design, the "pukka pies" of game studios: no compromise.

What better way to illustrate my point, apart from a fucking motorway metaphor, than a pdf file.

In Bungie land, changing the intermission between each shot with the Sniper Rifle from 0.5 seconds to 0.7 is enough to keep the motorway in a constant flow of "fun". The above PDF details Bungie's lead gameplay designer Jamie Griesemer's philosophy of breaking game design down to micro levels of detail, each of which build up to form one fun experience.

In the PDF Griesemer refers to the Bungie trademarked "30 seconds of fun" gameplay loop that if correctly utilised can keep providing audiences with gratifications in a continuous cycle. Referring back to the motorway metaphor, if the traffic keeps stalling then the driver is more likely to take the next exit, or in Bungie's case switch to a different game altogether. And it is Griesemer's job as Lead Gameplay Designer to keep the audience playing, at any cost.

In a recent Bungie podcast, when asked about the change in FOV (the players field of view) for Bungie's latest title, Sandbox designer Sage Merril discussed the many aspects that have to be considered when changing a shooters FOV, aspects that to me the ignorant player, had never crossed my mind. Firstly there is scale, what goes unnoticed in first person shooters is that the scale of the environments have to appear correctly within the players field of view, whilst also matching up to other minute elements of the game, such as grenade arc and line of sight. The field of view can also change a player's perception of speed, changing the entire pace of a game, a potentially catastrophic accident waiting to happen if not properly balanced.

By balancing these minute details, Bungie are able to stay rooted at the forefront of the first person shooter genre today, as it is these design philosophies and details which prevail above all else to keep the player engaged within the game. Fancy graphics and experience points may be a tasty substitute but they are no match for good old fashioned fun.

Saturday, 6 March 2010

To Be Or Not To Be?

Have you ever read those low budget fantasy fiction novels that allow the reader to make decisions surrounding the fate of the protagonist by choosing to wilfully skip to certain pre-determined pages? Well once, during a family holiday to Croatia, I did. Don't worry about your ability to comprehend what I am about to pontificate if you haven't though, they are shit, and I have already given them more phonemes than they deserve.

The problem with these novels is that they are woefully out of place in the context of their medium. A novels greatest attribute is its ability to engross the reader into a set narrative, with all the highs and lows that come with such a thing, not to have the reader turn to page 64 only to be eaten by a Goblin. These novels should never have been printed, instead they should have been videogames.

And in 2010, we finally have one. It's called Heavy Rain.

Upon inserting your disk into the PS3 you are prompted to remove the piece of paper contained within the games packaging and lead via onscreen instructions into a short tutorial on origami. From this point it is fairly transparent that Heavy Rain isn't like most games you have ever played. A risky move from Sony in the age of cookie cutter corridor shooters and cover systems.

Heavy Rain is an interactive narrative. Major events are pre-set, with the player free to manipulate scenes within it, controlling multiple protagonists in order to affect its progression, and ultimately conclusion. To do so the player must utilise a quirky and often befuddling control scheme, a challenge within itself at times.

Here is a handy example of one of the games scenes:

The player is controlling a journalist named Madison Paige in an attempt to gain evidence surrounding a notorious yet illusive child murderer known as the "Origami Killer".

I knock on the door of a man known to be linked with a property connected to the Origami Killer who also happens to deal in illegal medicinal substances. I am prompted on screen with a number of choices which will help me gain entry to his home in order to search for evidence. I pick the option showing interest in purchasing some medicine from the man, which is greeted with success as he invites me inside.

The creepy looking man offers me a glass of wine, I refuse, he insists, I suspiciously take the glass but decide not to drink it. The man notices my stubborn attitude towards not drinking his beverage and reluctantly slides off to fetch the medicine I claimed I required. This is my chance, I am free to snoop around his home. Tense, fast paced music begins to play, i know I don't have long before he returns.

His bathroom reveals nothing, apart from a lack of personal hygiene. The music is going at a faster tempo now and I know I am running out of time to find a lead, I even toy with going back to the living room where he left me in fear of him discovering my real intentions, and the consequences that would arise from that. But I plough on like the investigative journalist I am controlling and enter the mans bedroom. Big mistake. I twist the analogue stick to open his cupboard which reveals an abundance of surgical gowns. Fuck, this guy is a creep, the atmosphere and context has me freaked out. I want to leave. I exit the room but the camera teases me with one last door at the end of the corridor. I know I shouldn't, he will be back any moment, but I can't resist. As I enter this last mysterious room I am hit on the back of the head by the man. The screen cuts to black as I fall unconscious.

I won't spoil any more for you but I imagine you get the idea. What is interesting is everything here was a cognitive choice by me, the player. One problem the old fantasy novels faced was that it would take the player to a situation and then give them the false veneer of choice, "George took the sword and ran at the group of Goblins, turn to page 46 to fight the one on the left, turn to page 32 to fight the one on the right". Heavy Rain lets you steer clear of the conflict altogether.

Heavy Rain isn't free from its own identity crisis however. The opening 30 minutes task the player with brushing their teeth, having a shave and taking a shower. This may be well suited to some forms of entertainment, but perhaps not one with a 12 - 24 average target audience. It had me wondering why I was dedicating my time to something I could well accomplish in real life, without having to wrestle the worlds shittiest control scheme.

After all, is that not the point of entertainment itself? Do you think drug dealers in Baltimore get home and stick The Wire on? Do you think, technology permitted, that between beachhead assaults and evading machine gun fire, soldiers in World War 2 would have played some Call of Duty to pass the time?

Heavy Rain is not perfect. It is a promising template for a more mature experience than one currently existing within videogames today, and a welcome change from the shooter saturated market currently dominating the industry. Let's hope the audience can mature alongside it.

The problem with these novels is that they are woefully out of place in the context of their medium. A novels greatest attribute is its ability to engross the reader into a set narrative, with all the highs and lows that come with such a thing, not to have the reader turn to page 64 only to be eaten by a Goblin. These novels should never have been printed, instead they should have been videogames.

And in 2010, we finally have one. It's called Heavy Rain.

Upon inserting your disk into the PS3 you are prompted to remove the piece of paper contained within the games packaging and lead via onscreen instructions into a short tutorial on origami. From this point it is fairly transparent that Heavy Rain isn't like most games you have ever played. A risky move from Sony in the age of cookie cutter corridor shooters and cover systems.

Heavy Rain is an interactive narrative. Major events are pre-set, with the player free to manipulate scenes within it, controlling multiple protagonists in order to affect its progression, and ultimately conclusion. To do so the player must utilise a quirky and often befuddling control scheme, a challenge within itself at times.

Here is a handy example of one of the games scenes:

The player is controlling a journalist named Madison Paige in an attempt to gain evidence surrounding a notorious yet illusive child murderer known as the "Origami Killer".

I knock on the door of a man known to be linked with a property connected to the Origami Killer who also happens to deal in illegal medicinal substances. I am prompted on screen with a number of choices which will help me gain entry to his home in order to search for evidence. I pick the option showing interest in purchasing some medicine from the man, which is greeted with success as he invites me inside.

The creepy looking man offers me a glass of wine, I refuse, he insists, I suspiciously take the glass but decide not to drink it. The man notices my stubborn attitude towards not drinking his beverage and reluctantly slides off to fetch the medicine I claimed I required. This is my chance, I am free to snoop around his home. Tense, fast paced music begins to play, i know I don't have long before he returns.

His bathroom reveals nothing, apart from a lack of personal hygiene. The music is going at a faster tempo now and I know I am running out of time to find a lead, I even toy with going back to the living room where he left me in fear of him discovering my real intentions, and the consequences that would arise from that. But I plough on like the investigative journalist I am controlling and enter the mans bedroom. Big mistake. I twist the analogue stick to open his cupboard which reveals an abundance of surgical gowns. Fuck, this guy is a creep, the atmosphere and context has me freaked out. I want to leave. I exit the room but the camera teases me with one last door at the end of the corridor. I know I shouldn't, he will be back any moment, but I can't resist. As I enter this last mysterious room I am hit on the back of the head by the man. The screen cuts to black as I fall unconscious.

I won't spoil any more for you but I imagine you get the idea. What is interesting is everything here was a cognitive choice by me, the player. One problem the old fantasy novels faced was that it would take the player to a situation and then give them the false veneer of choice, "George took the sword and ran at the group of Goblins, turn to page 46 to fight the one on the left, turn to page 32 to fight the one on the right". Heavy Rain lets you steer clear of the conflict altogether.

Heavy Rain isn't free from its own identity crisis however. The opening 30 minutes task the player with brushing their teeth, having a shave and taking a shower. This may be well suited to some forms of entertainment, but perhaps not one with a 12 - 24 average target audience. It had me wondering why I was dedicating my time to something I could well accomplish in real life, without having to wrestle the worlds shittiest control scheme.

After all, is that not the point of entertainment itself? Do you think drug dealers in Baltimore get home and stick The Wire on? Do you think, technology permitted, that between beachhead assaults and evading machine gun fire, soldiers in World War 2 would have played some Call of Duty to pass the time?

Heavy Rain is not perfect. It is a promising template for a more mature experience than one currently existing within videogames today, and a welcome change from the shooter saturated market currently dominating the industry. Let's hope the audience can mature alongside it.

Saturday, 20 February 2010

Hey Bro, Fancy Shooting Some Terrorists?

Bro-operative. Bromance. These are just a couple of adjectives that could be used to describe the nature of Army of Two: 40th Day. A game where you and a friend (Biological or Artificial) need to essentially, as the name suggests, become a walking, shit talking army of two.

The plot unfortunately is fairly non-existent, which should come as no surprise given the game’s target audience, no offense intended. And whatever plot is present is unfortunately too quiet to hear. Yes quiet. During the games development cycle the developers forgot to turn the volume up during any scene of narrative worth whatsoever. This leaves the player in an apocalyptic rendering of Shanghai with no context at all to fuel your actions, in fact, upon completion me and my bro-op partner had literally no fucking clue what had just ensued, minus the asstastic gameplay.

But on the bright side, we did learn that EA Montreal was the first development studio comprised solely of deaf people.

So with the absence of a story, the game really needed some top calibre, highly polished, eternally fun gameplay to shine through the bullshit and make you forget those initial criticisms. And guess what, it doesn’t accomplish that one either. A third person shooter with a clunky aiming system is like a racing game with cars made out of cheese, it’s doomed to failure, just like Army of Two. Not to mention the game has an unintuitive cover mechanic that screams, “What the fuck” at you whenever you attempt to hide from the sheer number of bullets en route to your face.

However, amid this torrent of shit lies a silver lining. A single bubble of fun that has transcended all else to rise above the crap. The game handles co-operative play really well. Whether that be a system that allows players to draw fire away from their buddy in order to co-ordinate an attack, or whereby one player can falsely surrender, luring the gullable, artificially unintelligent terrorists into believing your cowardice whilst your partner conveniently dispatches them. It’s fair to say that the most original aspects of Army of Two come from these co-operative elements and when played with a friend the game isn’t shit, heck, it could even be described as “enjoyable”.

Had I not played Army of Two: 40th day with my friend this post would not exist. I would have failed to experience the single redeeming quality of the game, been exposed to a flood of derivative level design, combat and an overall sense of shit and proceeded to dismiss it as a dreadful videogame, which if experienced in tandem with a bro, it’s not.

The plot unfortunately is fairly non-existent, which should come as no surprise given the game’s target audience, no offense intended. And whatever plot is present is unfortunately too quiet to hear. Yes quiet. During the games development cycle the developers forgot to turn the volume up during any scene of narrative worth whatsoever. This leaves the player in an apocalyptic rendering of Shanghai with no context at all to fuel your actions, in fact, upon completion me and my bro-op partner had literally no fucking clue what had just ensued, minus the asstastic gameplay.

But on the bright side, we did learn that EA Montreal was the first development studio comprised solely of deaf people.

So with the absence of a story, the game really needed some top calibre, highly polished, eternally fun gameplay to shine through the bullshit and make you forget those initial criticisms. And guess what, it doesn’t accomplish that one either. A third person shooter with a clunky aiming system is like a racing game with cars made out of cheese, it’s doomed to failure, just like Army of Two. Not to mention the game has an unintuitive cover mechanic that screams, “What the fuck” at you whenever you attempt to hide from the sheer number of bullets en route to your face.

However, amid this torrent of shit lies a silver lining. A single bubble of fun that has transcended all else to rise above the crap. The game handles co-operative play really well. Whether that be a system that allows players to draw fire away from their buddy in order to co-ordinate an attack, or whereby one player can falsely surrender, luring the gullable, artificially unintelligent terrorists into believing your cowardice whilst your partner conveniently dispatches them. It’s fair to say that the most original aspects of Army of Two come from these co-operative elements and when played with a friend the game isn’t shit, heck, it could even be described as “enjoyable”.

Had I not played Army of Two: 40th day with my friend this post would not exist. I would have failed to experience the single redeeming quality of the game, been exposed to a flood of derivative level design, combat and an overall sense of shit and proceeded to dismiss it as a dreadful videogame, which if experienced in tandem with a bro, it’s not.

Sunday, 14 February 2010

Economic Imperative

The problem with entertainment nowadays is that the need to make money usurps the need to entertain. Sure, nobody wants to construct something unentertaining, however the need to make money will have a significant effect on the entertainment provided. Stupid fucking capitalism.

Take Bioshock 2 for example. The original holds more artistic merit in my opinion than Mona Lisa's slutty smile, and in fact presents a story as encapsulating as anything I have ever been exposed to. Partly because the twist was so twisty, but mostly because instead of wrapping a linear story within a non-linear experience, it understood that this just could not be done, and in fact video games weren't actually films in burly disguises. Irrational Games effectively fired a cum shot onto the video game industry's metaphorical chin.

Did Leonardo Da Vinci go out and produce a sequel to the Mona Lisa two years after he painted the original, perhaps with a speck of tit showing to please those freaky art lovers? Did he shit. He knew that the original was so revered, whatever he was to produce in direct succession to the original was never going to hold the same artistic value. Perhaps those economic dildos within the board room at 2K should have thought about that before giving the green light to Bioshock 2 then. Oh wait, they did, and they laughed it off. Who gives a fuck about artistic value when you have money, maybe now you will understand my point.

Bioshock 2 has much improved fundamental gameplay tweaks over the original. If you were locked in a room with no past exposure to the two games, a magnum pointed at the side of your brain, and told to select which one was the better game, a sane person would surely select the sequel. However, this is missing the point. The original had such an engaging narrative and a world so fresh and alien to the player that it felt perfect. The sequel therefore looses all such charms, leaving the player with a sharp stench of repetition and a lingering scent of deja vu. 2K too missed the point.

Take Bioshock 2 for example. The original holds more artistic merit in my opinion than Mona Lisa's slutty smile, and in fact presents a story as encapsulating as anything I have ever been exposed to. Partly because the twist was so twisty, but mostly because instead of wrapping a linear story within a non-linear experience, it understood that this just could not be done, and in fact video games weren't actually films in burly disguises. Irrational Games effectively fired a cum shot onto the video game industry's metaphorical chin.

Did Leonardo Da Vinci go out and produce a sequel to the Mona Lisa two years after he painted the original, perhaps with a speck of tit showing to please those freaky art lovers? Did he shit. He knew that the original was so revered, whatever he was to produce in direct succession to the original was never going to hold the same artistic value. Perhaps those economic dildos within the board room at 2K should have thought about that before giving the green light to Bioshock 2 then. Oh wait, they did, and they laughed it off. Who gives a fuck about artistic value when you have money, maybe now you will understand my point.

Bioshock 2 has much improved fundamental gameplay tweaks over the original. If you were locked in a room with no past exposure to the two games, a magnum pointed at the side of your brain, and told to select which one was the better game, a sane person would surely select the sequel. However, this is missing the point. The original had such an engaging narrative and a world so fresh and alien to the player that it felt perfect. The sequel therefore looses all such charms, leaving the player with a sharp stench of repetition and a lingering scent of deja vu. 2K too missed the point.

Wednesday, 10 February 2010

Belated Review of Modern Warfare Two

How does a developer go about crafting the sequel to one of the decades most appreciated videogames? Call of Duty 4: Modern Warfare launched to instant success, eventually topping over 10 million sales across multiple platforms. This was a double-edged sword for developer Infinity Ward; they created the current generations most influential first person shooter, yet they themselves must go one better and produce a sequel worthy of the name. Modern Warfare 2 is their much-anticipated attempt.

The campaign kicks off with the player controlling Private First Class Joseph Allen, a US army ranger based in Afghanistan as he takes part in a Humvee assault through an Afghan city, reminiscent of American drama “Generation Kill”. Recognised for his achievements, Private Allen is then whisked off to join Task Force 141, recruited to covertly infiltrate a known terrorist threat lead by the game’s primary antagonist Vladimir Zhakarov. The game then presents a twist, one which provides the narrative fuel to drive the player through to the inevitable conclusion.

In typical Call of Duty style, the game ping pongs between different characters during the story in order to tell each individual section of the narrative. This can leave the game’s pacing feeling flat, often deflating the player when he is stripped of his task force 141 rank and thrown back into the ordinary boots of Private James Ramirez, a generic soldier tasked with performing tedious objectives. For example, whilst one mission has you assaulting a military base under the stealthy cover of a blizzard, the next sees you escorting an Armoured Personnel Carrier through the suburban streets of Eastern America. This stark contrast can be a hindrance to the player’s enjoyment, especially considering developer Infinity Ward’s ability to craft such memorable set pieces, instead forcing you to rely on such genre clichés as an escort mission. Despite the drop in calibre, these set pieces are still wonderfully crafted, with one tasking the player to retake the Whitehouse from Russian invasion, a visually emotive experience that encapsulates the game’s sombre narrative.

The narrative itself is standard action game fare. A slightly unrealistic scenario littered with plot holes but accepted due to its all out epic nature. A tepid Russia un-cover a reason to invade the United States of America whilst the whole world hangs on the precipice of nuclear fallout. I think you’ll agree an exhilarating prospect, and unfortunately in today’s post 9-11 society an ever more plausible one. Filled with multiple twists it is the perfect accompaniment to the games fast paced gunplay.

Although inconsistent, the game really shines during its most intense moments. Fast paced, action packed and full of set pieces you will want to replay, the Singleplayer is nothing but excellent. Highlights include jumping from the corregated iron roof of a shanty Favela hut to reach the dangling rope of a rescue helicopter, and storming an Alcatraz esque prison culminating in a narrative twist most fans of the series can’t help but smile about. Furthermore, the games final sequence is arguably the most enjoyable moment, leaving players with a sweet taste upon completion and a heap of fond memories.

Upon completion of this 6 – 8 hour campaign the player is then introduced to Spec Ops; a co-operative two player mode which presents modified set pieces, some extracted from the campaign, some original, each thoroughly entertaining. The game remains challenging as the missions are varied whilst escalating in difficulty and intensity. Intelligent achievements task the player with completing each Spec Ops mission on the highest veteran difficulty, a challenge truly worthy of the gamerscore (or trophies depending on platform) it hands out. While challenging, the game is exploitable on the hardest missions, taking some of the fun away in exchange for virtual progress. Spec Ops is a “best of” selection from the Call of Duty series, thoroughly entertaining and a worthy addition to the series.

Of course, while these two modes are an enjoyable starter, the games main course is the multiplayer. If you were one of the millions that played Call of Duty 4 then things should be instantly recognisable. Each player can apply 2 perks to give them advantages in combat which help them to rank up so they can unlock special items and camouflage patterns. However this time Infinity Ward have increased the player’s already huge array of options. The range of killstreak rewards (selectable abilities gained after having achieved a certain number of kills before death) has over doubled, now offering the ability to airdrop a care package which enables the player a random ability, potentially a match winning one. The array of attachments which can bolster your weapons effectiveness have also seen a healthy increase, now featuring items such as a thermal scope for spotting enemies in low visibility environments.